A few years ago, I sent a friend a book chapter I’d been working on for months. Desperate for validation, I waited anxiously for a response. As the days passed, I convinced myself he hated it. Obviously, he was putting off telling me how bad it was. Two weeks later, the email arrived … with an attachment. My friend had completely rewritten the chapter. Not only that, he’d used tracked changes in Word, so it was a sea of red. As you can imagine, my heart plunged into my boots. I’d wanted him to say, “Goodness, Catherine, you’ve worked really hard on this. Well done.” As I hadn’t explained my requirement, he’d assumed I wanted extensive editorial input.

This quote from Thanks for the Feedback by Douglas Stone and Sheila Heen explains exactly why feedback can cause so much friction and despair:

“When we give feedback, we notice that the receiver isn’t good at receiving it. When we receive feedback, we notice that the giver isn’t good at giving it.” (p.3)

We’re often mismatched in our approach.

Heen and Stone identify three main types of feedback for us to distinguish between:

- Appreciative feedback - this is all about motivation and encouragement. “Great job - well done!” 🏆

- Coaching feedback - building skills and increasing capability. “You’re nearly there - now focus on this specific point.” ☝️

- Evaluative feedback - aligning expectations and benchmarking achievements. “This is where you are, and this is where you need to be.” 📊

Giving Feedback

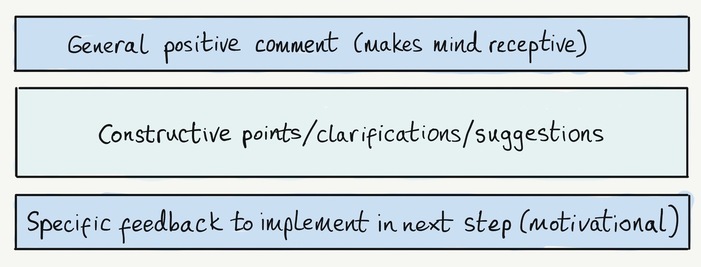

When giving feedback, we should check what’s required. Of course, we shouldn’t just say nice things, but launching into a litany of errors can be overwhelming. Most of us are attuned to the Feedback Sandwich (better known as the Sh*t Sandwich) where the criticisms are made more palatable with some encouraging words either side.

While some people at the receiving end (including me) prefer this approach, others just get annoyed with it: “Why are you giving me all this flannel? Just tell me what’s wrong with it!” But anyone lacking confidence might appreciate some encouragement first. I’ve seen many PhD researchers whose work is completely transformed by positive words and carefully chosen feedback. Blunt criticism, however valid, can simply reinforce imposter feelings.

There’s also a world of difference between written and spoken feedback. If someone is anxious, they’ll interpret neutral written feedback as critical, as it’s divorced from tone and body language. Although you meant those words to sound warm and encouraging, the receiver is picturing you stony-faced. Sending voice or video notes can really help.

Heen and Stone recommend asking yourself three questions before giving feedback:

- What’s my purpose in giving this feedback?

- Is it the right purpose from my point of view?

- Is it the right purpose from the other person’s point of view? (p. 42)

What does the receiver need right now? Three pages of corrections, or reassurance that they’re improving?

Requesting Feedback

When requesting feedback, be specific on what you need, e.g. “I’m struggling here and need some encouragement. Is this broadly going in the right direction?” (in other words, please don’t flag all the split infinitives). Or, “I’m about to submit this paper, do you think the argument is clear?”. If you’re dealing with someone who can’t resist the temptation to rewrite your draft, send them a PDF, rather than a Word document. That won’t stop determined tinkerers, but the additional friction is a handy deterrent.

As Stone and Heen point out, “Receiving feedback well doesn’t mean you always have to take the feedback. Receiving it well means engaging in the conversation skillfully and making thoughtful choices about whether and how to use the information and what you’re learning.” (Page 8) Feedback is like data: some of it is useful, while some of it can be safely discarded. Of course, feedback is always subjective.

When a publisher sent my book manuscript to three anonymous reviewers, I received three completely different verdicts. Reader 1 thought it was great and should be published without revision. Reader 2 thought it was good, but needed strengthening in specific areas. Reader 3 thought the book was terrible and needed rewriting completely. Same manuscript, three completely different verdicts. I love Stone and Heen’s description: “views are input, not imprint.” (p. 180) But, if someone takes the time to give you feedback, it’s important not to dismiss it wholesale.

Feedback can feel like a judgement on our worth. It’s important to not confuse your work with your identity. If feedback does feel personal, make sure you’re requesting specific comments on a piece of work, rather than asking, “How am I doing?”. A wobbly early draft doesn’t mean you’re not cut out to be a researcher or a writer.

Improving Feedback

We tend to assume that other people share our feedback preferences, or that there’s one approach for every situation. That’s where it goes awry. Also, feedback is usually perceived as one-way. We can help each other enormously by requesting feedback on our feedback. This also alters the dynamic so that feedback becomes more collaborative, rather than an exercise of power. After delivering feedback, ask if that’s what the receiver expected. Are they clear on what to do next? Are they feeling motivated, or deflated? Be clear that you genuinely want feedback and that this isn’t a trick.

Feedback sits at the intersection of two needs: “our drive to learn and our longing for acceptance. These needs run deep, and the tension between them is not going away.” (p. 8) This doesn’t mean we have always give people a gold star, rather that we should consider each situation carefully before deciding what kind of feedback is appropriate.

Somebody else would have been thrilled with the detailed feedback from my friend. I just wanted that gold star ⭐

Some of this content is adapted from my workshop Working with Your PhD Supervisor.

There’s also a blog post on implementing feedback from your supervisor.