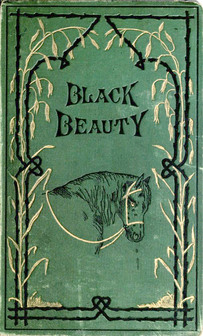

As you probably know, Black Beauty (1877) is the autobiography of a rather handsome horse, admirably translated from the equine by Anna Sewell. Less well-known is the fact that Sewell earned just £40 for the copyright of the phenomenally successful novel. It sold 100,000 copies in her own short lifetime, and has no doubt sold millions more since then. Sadly, she didn’t live long enough to cash in on her name. However, I think she’d be pleased if her tale resulted in even one horse receiving better treatment.

Black Beauty, a glossy and good-tempered colt, belongs to a succession of owners. Some are kind, some are indifferent, and a few are downright sadistic. He begins life in an idyllic meadow, frolicking with his friends Merrylegs and Ginger under the watchful eye of his wise mother. Years later, when suffering the misery of life as an over-worked cab horse, Black Beauty indulges in poignant memories of his early years.

Sewell uses the experiences of Black Beauty and his friends to highlight the often appalling treatment meted out to horses. In some cases masters are simply unfeeling, working their beasts into the ground; in others, the dubious dictates of fashion mean that their bodies are contorted by the likes of the notorious bearing rein, which seriously restricted head movement. Although this is a children’s book, Sewell does not hold back on the shocking reality of the injuries sustained. In a memorable early episode, the relentless pursuit of a hare results in the death of both horse and rider.

Whereas many anthropomorphic tales incline towards the mawkish, Sewell’s mission undercuts any sentimentality, but without detracting from a good narrative. Her exposé gave a boost to the newly formed RSPCA and greatly increased awareness of the treatment of animals. 13 years later, John Strange Winter (the pen name of Henrietta Stannard) featured the plight of the cab horse in her novel He Went for a Soldier, and was instrumental in persuading Fulham Borough Council to legislate against the use of broken-down animals.

Although the emphasis is very much on animal welfare, Sewell does occasionally draw parallels with the treatment of servants: someone who abuses a horse is probably not kindly disposed towards their other “subordinates”. Black Beauty wonders “if the beautiful ladies ever think of the weary cabman waiting on his box, and his patient beast standing, till his legs get stiff with cold.” He goes on to say “We horses do not mind hard work if we are treated reasonably” – a statement that might well be echoed by the shivering cabman.

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed this novel, especially having come to it about 30 years later than most folk. I’m far from horsey, but found myself completely engrossed in the story and seeing the world from the perspective of a quadruped, and one who uses phrases like “begging your pardon”.

A big thank you to Girlebooks for making available such a high-quality free Kindle edition of this text.