True crime isn’t usually my cup of tea, but I found myself completely transfixed by Elizabeth Jenkins’s Harriet (1934) last year. Based on the infamous Penge murder trial of 1877, the novel recounts the short life and pitiful death of Harriet Staunton, a middle-class woman with what we would now call ‘learning difficulties’. Although she struggled to read and write, Harriet took great pride in her appearance and enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle with a comfortable income. Her loving mother did everything to make Harriet’s life normal, never imagining her daughter would become the victim of a merciless fortune-hunter.

The charming but callous Louis Staunton quickly wooed Harriet, motivated by the knowledge that wives’ assets were assumed by the husband on marriage. Soon tiring of her odd behaviour, he paid his brother Patrick and sister-in-law Elizabeth to care for Harriet and their baby. Louis then promptly moved in with his lover, Alice. Harriet was subjected to intolerable cruelty, the facts of which became chillingly clear in the sensational trial that followed. Fortunately, Jenkins manages to convey the horror of Harriet’s story without relying on explicit descriptions of torments she suffered. This is very much a psychological thriller, and one told with great verve and insight.

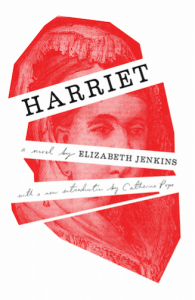

Valancourt Books has just published a new edition of Harriet and I was delighted that they asked me to contribute an afterword. While reading the trial proceedings and researching the background to the case was deeply uncomfortable, I felt that Harriet’s treatment says a great deal about the position of women in the nineteenth century and how easy it was to deny them subjectivity. Louis was able to take advantage of women’s legal vulnerability at the time and Harriet’s mother was powerless to prevent him. On marriage, Harriet’s considerable assets became his to do with as he pleased. She endowed him with all her worldly goods; he gave her nothing. In fact, it appears that Harriet’s plight lent impetus to the campaign for the Second Married Women’s Property Act, which finally allowed women to own property in their own name.

In my afterword, I also explain what happened following the trial, and how Queen Victoria became involved in this extraordinary case. The transcription of the trial is full of revelations, contradictions, and outright denials, all of which Jenkins deftly constructs into a taut and compelling story. Such is the veracity and intensity of her novel, Jenkins actually came to regret having written it. She felt uncomfortable with exploring a real-life case as fiction, and Harriet’s sufferings were particularly difficult to read following the horrors of the Second World War.

Notwithstanding the author’s reservations, Harriet remains a provocative and important novel. By placing her victim at the centre of the narrative, Jenkins gives Harriet the attention and respect she was denied as a wife.

For rights reasons, this edition of Harriet is currently only available in the US. For more information, please visit the Valancourt Books website.