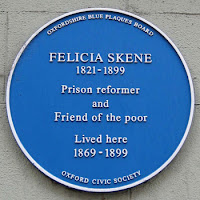

Felicia Skene (1821-99) was a philanthropist and writer. Born in Aix-en-Provence, she moved to Oxford during the tumult of Newman’s defection to Rome and was heavily influenced by High Anglicanism. Much of her writing was barely diluted Tractarian propaganda, but in Hidden Depths (1866) she exposes the prostitution rife in Oxford (thinly disguised as ‘Greyburgh’), and attacks the hypocrisy of those who blamed the ‘fallen’ women for the spread of venereal disease, rather than the men (and sometimes women) who exploited them.

The heroine of the novel is Ernestine Courtenay, who sets out to save the sister of a girl her feckless brother seduced and abandoned. Along the way, she discovers the appalling iniquity behind the seemingly respectable facades of the homes and the university. Skene originally published the novel anonymously, attaching her name only to a later edition. There was an appalled reaction, particularly from the inhabitants of ‘Greyborough’ who refused to countenance the idea of any shenanigans, particularly in their hallowed seat of learning. The author maintained that the graphic scenes were based on eyewitness accounts, and subtitled the novel “Veritas Est Major Charitas” – truth is the greater charity. As a regular prison visitor she had met many of the women she was portraying, and was in no doubt that they were victims, rather than the wicked hussies of popular opinion.

Skene was writing at the time of the Contagious Diseases Acts (1865 and 1866), invidious legislation that demonised often helpless women in an effort to protect those who abused them. Skene arguably goes further than any author of the day in depicting so vividly the specious nature of middle-class respectability. Contrary to the claims of many detractors, this was not an attack on men, as the most disturbing episode in the novel is when the brothel keeper Mrs Dorrell burns alive the two children of one of her “tenants” who has absconded without paying the rent.

Skene is certainly no proto-feminist. In the early chapters, Ernestine (who appears to be representative of the author’s views) is careful to distance herself from the nascent women’s movement: “And as to the sect who want to raise women out of their natural position, I utterly detest and abjure their opinions; they are contrary to laws both human and divine, in my opinion.” Nevertheless, she does espouse female solidarity. As Lillian Nayder explains in her introduction: “sisterhood resonates with both political and religious meaning and provides her female characters with an escape from sexual oppression as well as spiritual falleness.” Skene’s agenda is essentially religious, exposing hypocrisy and presenting her High Church views. Ernestine tries mostly in vain to encourage Christian forgiveness in those who are in a position to help the women she encounters.

Having already spent 20 years visiting the friendless and forgotten in Oxford’s prisons, Skene was officially appointed “lady visitor” by the government in 1878. Her abundant humanity also brought her close to contemporary writers such as Mrs Humphry Ward and Frances Power Cobbe, who shared her philanthropic zeal, if not her religious orthodoxy. Her profile was further raised in 1885 when an MP recognised the “unusual power” of Hidden Depths and thought it should be republished. It went on to sell 30,000 copies.

The novel is hard to categorise, spanning as it does the sensation school and Tractarianism, and the apparent contradictions thereof fuelled much of the criticism. Nayder’s introduction is perspicacious in showing how multivalent approach is more rewarding than any attempt at pigeonholing the text. Although there are compelling episodes in the plot, this is not an easy read, either in terms of the subject matter or the format. The style is highly polemical and the narrative frequently sags under the weight of the religious dogma. However, it is an important document, and a brave venture from a woman who many thought should remain silent.

Hidden Depths by Felicia Skene. Edited by Lillian Nayder (Pickering & Chatto, 2004)