Even when we start out with a clear plan, it’s easy to end up with rambling draft. We know there’s an argument lurking within, but we’re darned if we can find it. While every writer is different, nearly everyone benefits from the technique of reverse outlining. I think it’s the best way to improve the flow of your argument and produce a coherent manuscript or thesis. There are many different approaches to this technique and there’s no right way of doing it. I’ll share my approach with you, which you can then adapt.

Step One

Print a draft of your completed chapter (I think it’s easier to work on a physical copy).

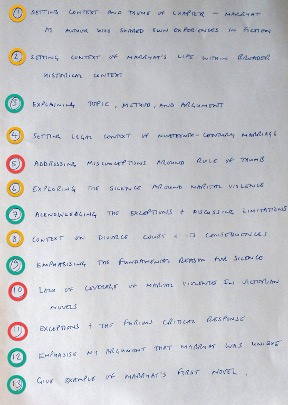

Number the paragraphs in the margin.

For each paragraph, write a concise bullet point summary (it should fit on one line and describe the purpose of that paragraph, or summarise the argument, e.g. providing historical context on XXXXX, explaining theory of XXXXX, outlining the chapter).

You now have a compact list, which is much easier to work with than scrolling back and forth through a monster Word document. It’ll take you 2-3 hours to reverse-outline a 10,000-word draft, but it’s time well spent. Although you could use a chatbot like ChatGPT or Claude, doing it yourself forces you to engage critically with what you’ve written.

Step Two

Next, scan through your bullet list and remain alert for the following:

- Are your paragraphs following a logical sequence? Or are you hopping around?

- Are there any duplications? We all have a tendency to say the same thing in slightly different ways.

- Can you see gaps where you need to add a segue? Or maybe a subheading to indicate a change of topic?

- Are there giant leaps that require additional context? Are you taking your reader with you, or leaving them behind?

- Can you spot digressions that might confuse the reader? Have you got excited about a related topic?

- Are there any paragraphs that are doing too much work and should be divided? If your bullet point is long and complicated, this suggests a paragraph that needs simplifying.

- Or are there some paragraphs that are lacking a specific point and can be ditched? Did you struggle to find a point to the paragraph? These chunks often represent our thoughts. Although they were necessary in working out our overall argument, they’re not required in a final version.

Step Three

Edit the bullet point list by getting everything in the right order. Also, flag any necessary insertions, deletions, or consolidations. You can then use the revised list as a model for your draft. Make a copy or a backup first, just in case you regret some of the changes. Also, ensure you cut-and-paste paragraphs when you’re moving them, rather than copying – otherwise you can end up with duplicates. You can add comments to record what you’ve done, too.

Step Four

This one is optional.

It’s common for us to rely too much on secondary sources and using quotations from more established academics to make an argument, especially when we’re early career academics Consequently, our own voice gets lost, and the thesis becomes a synthesis. To ensure your voice is evident, you need to remove some of that scaffolding.

Using your reverse outline bullet point list, devise a colour-coded scheme to flag the different types of writing in your draft. For example:

- RED = secondary sources

- AMBER = context

- GREEN = original argument/findings/conclusions, etc.

You could simply circle each bullet point with the corresponding colour or use a highlighter pen on the text itself. Either way, you’ll quickly get a sense of the balance in your chapter. Is it a sea of red? There’s no right balance between secondary sources, context, and originality, so spend some time thinking what might be appropriate for your book. Perhaps you could prune a secondary source from a six-line block quote down to a one-sentence inline quote. Then you’ve got more room to add your own insight.

Reverse outlining is beautifully simple, but it’s also time-consuming. If you need to get a sense of how long it’ll take for your book or thesis, try it out on a small sample of your writing, say 2,000 words. You can also use this technique to understand how other people structure their work. If you’ve read a piece of academic writing that was easy to follow, I’m willing to bet the author spent some time on reverse outlining.